Government Systems

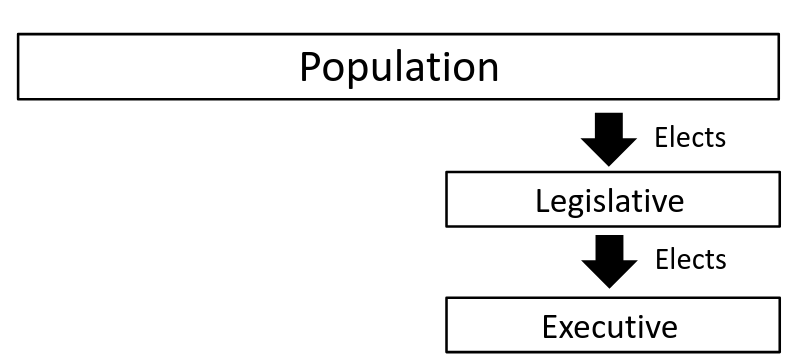

Basic distinction

- How is the leader of the executive elected? How can the leader of the executive be removed?

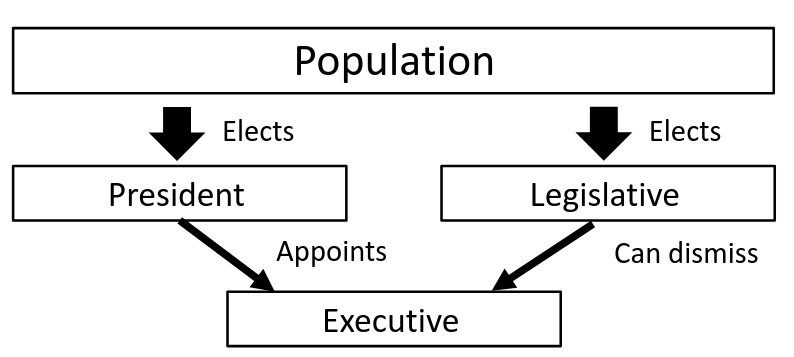

- Presidentialism: Elected by the population, cannot be removed.

- Parliamentarism: Elected by parliament, can be removed by parliament.

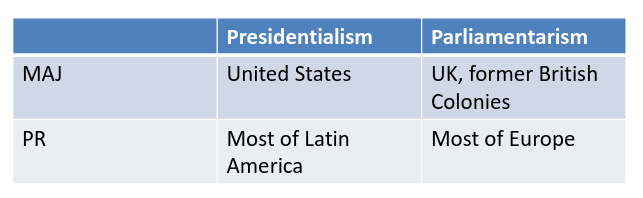

Relationship to electoral systems

- The distinction between MAJ and PR concerns parliamentary elections.

- Presidential elections are always majoritarian (sometimes with simple majority, sometimes with runoff, sometimes with complications such as the electoral college in the US).

- Parliamentary elections in a presidential system can be majoritarian (USA, France) or proportional (Brasil, France 1986).

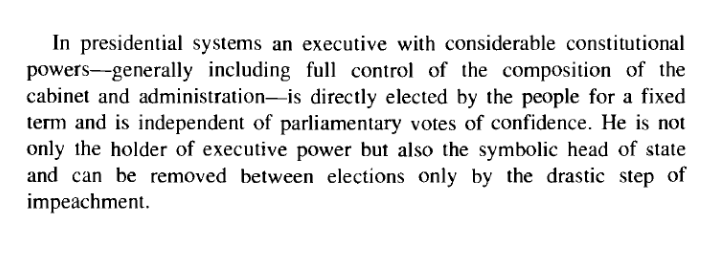

Presidentialism

- Direct election of the president, who is head of government and head of state (→ a Republic)

- President is independent from the parliamentary majority, which is elected separately → dual legitimacy.

- Length of terms of president and parliament are fixed. (Some presidential systems allow recall elections, but no recall election has ever succeeded in removing a national executive from office).

- Ministers are nominated by the president and responsible to him.

- President and parliament are jointly responsible for making laws (with considerable variation in detail).

Variations

- The United States:

- Veto of the president: if the president refuses to sign a law, a 2/3 majority in both houses of Congress is necessary to overrule him.

- President cannot dissolve Congress.

- France (semi-presidentialism):

- President has no veto power.

- But can dissolve the Assemblée Nationale.

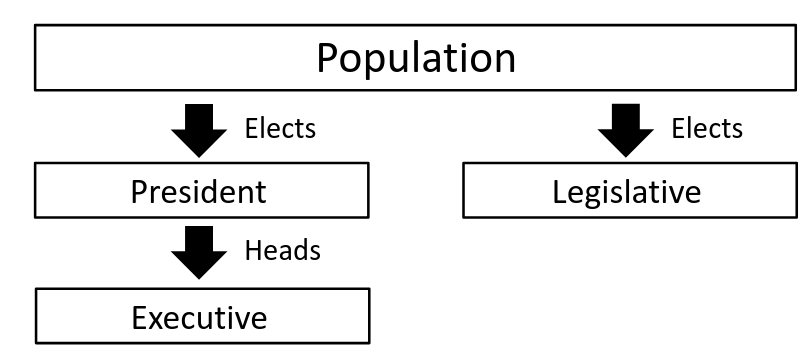

Separation of powers

Core idea→separation of main state functions, checks and balances:

- Executive and legislative are elected directly and separately → both have direct democratic legitimacy.

- The legislative introduces laws (in US, laws often named after their sponsors (the Sherman antitrust act).

Illustration

In the US, the government is not physically present in the parliament (annual exception: State of the Union speech where parliament is where the whole government lives).

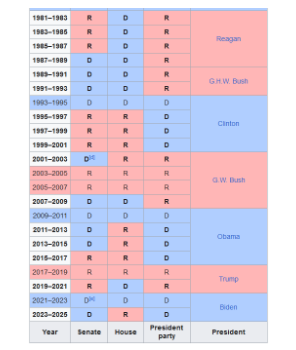

Divided government

- It is possible that the President’s party also has a majority in parliament.

- If not: divided government (very common in US, used to be rare in France→Cohabitation).

- Importance of timing of legislative elections.

- Concern: Gridlock.

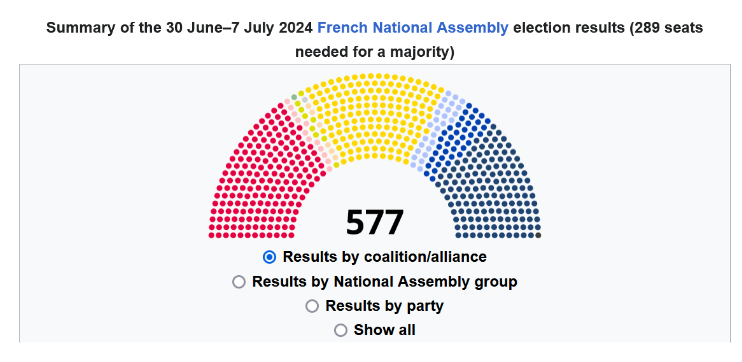

Semi-Presidentialism (France)

In France there is a president and a PM dependent on the president and Parliament, de Gaulle made this constitution kind of thinking as himself as the president. The president remains more powerful (controls foreign policy, etc…).

In France there is a president and a PM dependent on the president and Parliament, de Gaulle made this constitution kind of thinking as himself as the president. The president remains more powerful (controls foreign policy, etc…).

- Macron appointed Sebastien Lecornu as his prime minister.

- As long as there is no majority against him (vote of no confidence), he can remain in office.

- When the prime minister loses a vote of no confidence (Barnier, Bayrou), the president has to appoint a new prime minister.

- In traditional cohabitation (Chirac/Jospin), the prime minister has a governing majority.

Since Macron dissolved the assembly, there has been no clear majority that’s stable. Plus, there is no tradition of making coalitions in France.

Since Macron dissolved the assembly, there has been no clear majority that’s stable. Plus, there is no tradition of making coalitions in France.

Parliamentarism

- Separation of head of government and (largely ceremonial) head of state.

- Prime minister is elected by parliament, the only directly elected body.

- Parliament can be dissolved and new elections be called.

- Ministers are responsible to parliament (to different degrees).

- Government controls the agenda of parliament.

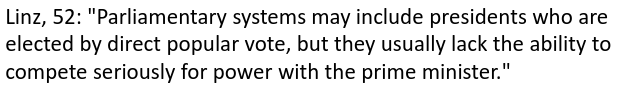

- Parliamentary systems have a head of state that is not the head of the executive.

- They represent the country, visit the olympic team, etc…

- The head of state can be a monarch, can be elected by the people, or can be elected by a special body.

- Important: The head of state has symbolic functions but no executive power!

Dissolution of parliament

- Government can often dissolve parliament.

- Parliament can withdraw confidence from the government, either forming a new government or triggering new elections.

- (As so often, Switzerland is quite unique).

Fusion of powers

- Only legislative is directly elected, executive emerges from legislative.

- Laws emerge from the executive, are introduced to parliament by the government.

- In many (not all) systems, the prime minister (and sometimes cabinet members) need to be members of parliament.

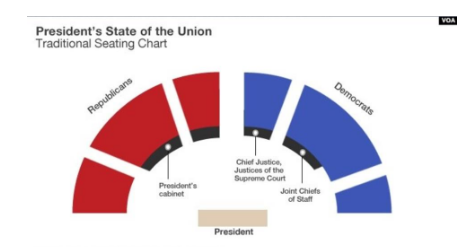

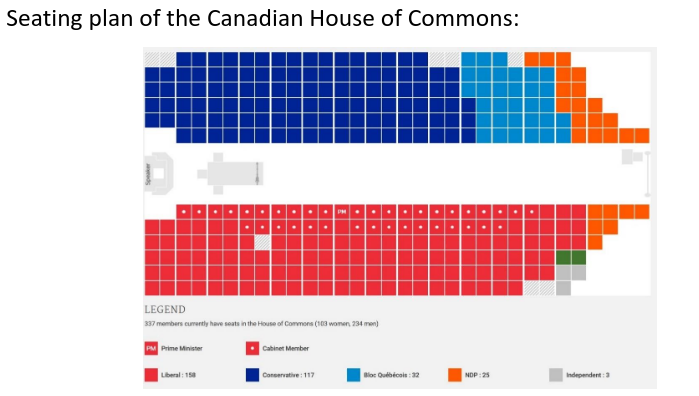

Illustration

Government usually sits at the front of their party’s sector.

Government usually sits at the front of their party’s sector.

Parliamentarism: Minority government

- It is possible that the prime minister’s party or coalition does not have a majority in parliament.

- This arrangement is more fragile than divided government (depending on the provisions for toppling a prime minister).

- However, it is also less prone to Gridlock → governing with changing majorities, new elections.

Consequences

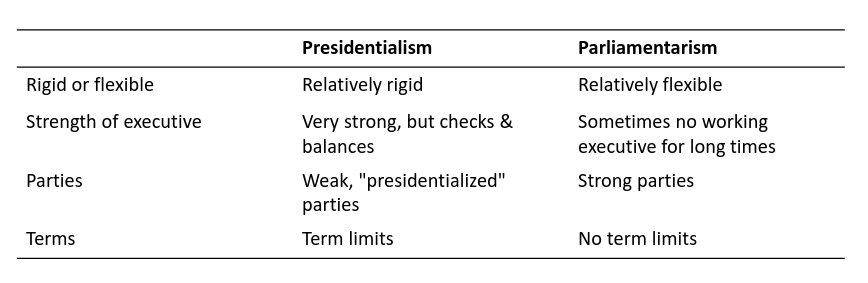

Rigidity

- Presidentialism: Fixed term of president, fixed term of legislature

- Parliamentarism: Can create new governments or call new elections in response to major shocks.

- Rigidity as a disadvantage (Linz below).

- What if president dies, a party suddenly does better in polls, etc…

- Rigidity as an advantage → Parliamentary systems can be prone to instability, e.g. Italy.

Strength of the executive

Presidentialism

- Executive does not need confidence of parliament → quite independent.

- Has direct democratic legitimacy.

- Direct access to the population.

Parliamentarism

- Parliaments not always able to agree on an executive or laws (coalition case).

- Belgium went without an elected government for 589 days in 2010-11.

- Italy had 45 prime ministers since WW2.

- But: Very strong if single-party majority government (UK).

Parties

- E.E. Schattschneider: The political parties created democracy and modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties. (E. E. Schattschneider, Party Government, New York, 1942, p. 53.)

- The actor who organises the fusion of powers are parties.

- The actor who makes separation of powers at all workable is parties.

- More on parties in session 10.

Presidential systems often have weak parties (France, US).

- Personalisation induces open primaries for selecting candidates for the Presidency, weakening the party.

- Presidents who don’t need the confidence of parliament also don’t need the confidence of their party!

Parliamentary systems traditionally have strong parties.

- Parties willing and able to depose unpopular leaders.

- But: parties are in decline everywhere.

The question of term length

- Presidential system typically impose term limits (if they don’t president might think he should be king):

- Two terms (USA).

- Two terms, then one break intermission, then another two terms (Argentina, Brasil → Lula da Silva).

- Two, non-consecutive terms (Chile).

- Unlimited, non-consecutive terms (Uruguay).

- A single term (Mexico).

- No limits in parliamentary system, can lead to very long prime ministerships (people can in many cases reelect someone indefinitely):

- M. Rutte, Netherlands, 2010-2024.

- A. Merkel, Germany, 2005-2021.

- F. Gonzalez, Spain, 1982-1996.

- P. Trudeau, Canada, 1968-1984.

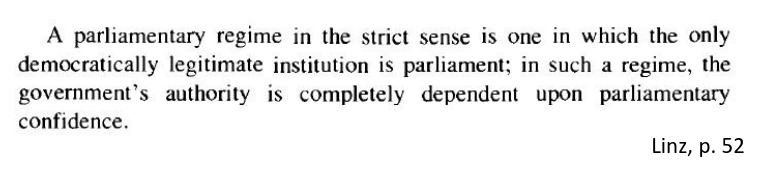

Linz, fundamental claim

Instead of richness promoting democracy here we try to argue its parliamentarism that does.

Instead of richness promoting democracy here we try to argue its parliamentarism that does.

Further arguments

- Zero-sum game: too clear separation of winners and losers→ polarisation (p. 56)

- The plebiscitarian component and presidential style: appealing directly to the people, anti-institutional (p. 61)

- The problem of dual legitimacy → unclear who can claim to represent the will of the people (arrogance, populism) (p. 62).

- Term limits turn repeated games into one-shot games (radical and irrational policies) (p. 65).

Reactions to Linz

- Scott Mainwaring and Matthew S. Shugart. 1997. “Juan Linz, Presidentialism, and Democracy: A Critical Appraisal”. In: Comparative Politics, 29(4), pp. 449-471.

- the superior record of parliamentarism is in part an artifact of where it has been implemented.

Mainwaring and Shugart

Theoretical argument:

- Parliamentary systems also know the problem of dual legitimacy, e.g. if there are two chambers (bicameralism).

- There is a tension about the role of the president in parliamentary systems. To be an arbiter, it needs competencies. But these contain the danger of constitutional conflict.

- Winner-take-all-character depends on electoral system, not on presidentialism.

- Could the USA reduce polarisation trough PR? Empirical argument:

- Parliamentarism often introduced in rich (European) or small, relatively homogenous countries.

- Presidentialism more often introduced in poorer, and bigger, more heterogeneous (Latin American/African) countries.

- Role of colonisation (looking at the example of their colonisers like France or some with their liberators such as the USA).

- Also appears to be a solution to instability.

Endogeneity

Linz says that presidential countries become more politically unstable. What if it is the other way around: Politically unstable countries decide to introduce presidentialism (e.g. because they hope a strong leader will bring more stability?). ⇒ Very similar to the problem in Döring/Manow. ⇒ A core problem of empirical analyses in comparative politics.