Electoral Systems

The institutionalist approach

Formal institutions as the main factors that explain outcome differences between countries. Differences such as:

- Elements of the political system: the number of parties, the share of female MPs, how often government changes, etc…

- Outputs (policies): immigration policies, the size of public debt, the provision of childcare by the state, climate protection policies, etc…

- Outcomes: economic growth, the degree of economic inequality, social capital and social trust, etc…

Differences between electoral systems

Historically many questions

- Who has the right to vote?

- How are elections conducted? Is the ballot secret?

- How often are elections taking place?

Main question differentiating electoral systems in consolidated democracies today

- How are votes translated into outcomes (seats)?

Main distinction in vote translation

Majoritarian systems – Single Member Districts (SMD)

- First Past the Post (Plurality).

- Alternative vote.

- Runoff (France).

Proportional systems – Multimember districts

- Party-list Proportional Representation.

- Mixed-Member Proportionality (Germany).

- Single Transferable Vote (Ireland).

Majoritarian Systems

- The older system.

- One seat per district (constituency).

- The district winner gets the seat, everybody else gets nothing.

- Winning requires a plurality (US, UK) or majority (France, with runoff).

- Results often depicted by a map (since only interested in district winner).

Proportional Systems

- Introduced mainly after World War I.

- Several members per district (Switzerland: UR, OW, NW, GL, AR, AI: 1 seat, ZH: 35 seats).

- Extreme case: single, nationwide district (Israel, NL).

- Parties get seats in proportion to their votes (in each district, e.g. each canton).

- Different formulas for distributing seats (Sainte-Laguë, D’Hondt etc. pp.).

- Results often depicted by a bar chart (since interested in many/all parties).

Closed list or open list

Closed list or open list:

- Closed list: party draws up a list before the election; voters vote for party; if party receives 6 seats, the first six candidates from the list get those seats.

- Open list: Voters have preference votes for specific candidates on the list of their favoured parties. Thus, they can affect which of the party’s candidates get those 6 seats.

Consequences of proportionality

A difference that is already in the name

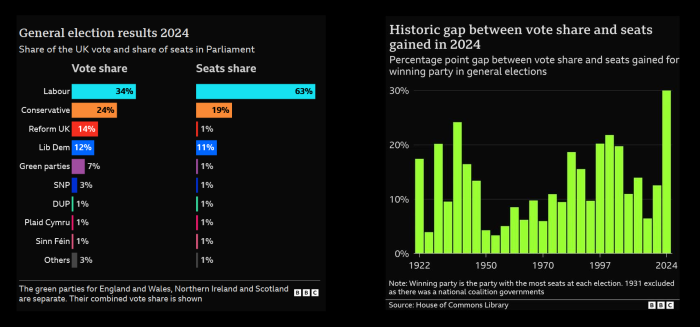

- PR: a party’s share of seats in parliament is (roughly) proportional to its share of votes.

- MAJ: strong disproportionality between votes and seats, the biggest party is typically strongly overrepresented (due to winning many districts narrowly), the other parties are underrepresented.

- Split vote in UK→Labour easily wins many districts relative to their votes.

Exceptions

- Regional parties, thanks to the local concentration of their vote.

- Pure two-party-systems can end up pretty proportional (50% of the vote → 50% of the seats for each party).

Other consequences

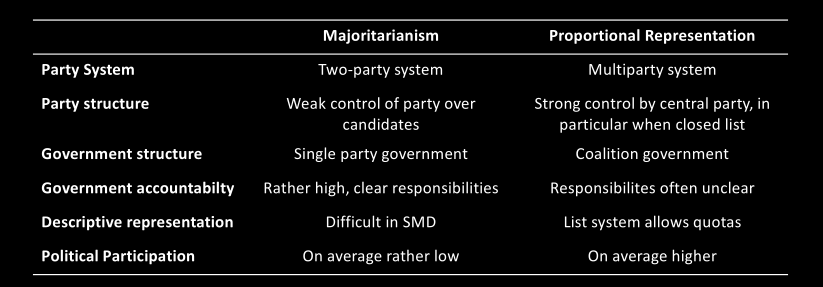

Party systems

- PR systems tend to have multiparty systems

- Fragmentation: How many parties are there effectively?.

- Crucial role of formal or informal thresholds:

- Formal thresholds: seats are only allocated when a party receives a certain minimum share of votes, e.g. 4% (Austria), 5% (Germany) or 7% (Turkey).

- Effective thresholds: The number of seats per district works as an effective threshold. E.g. Ireland: 3-5 seats per district, effective threshold of about 10%.

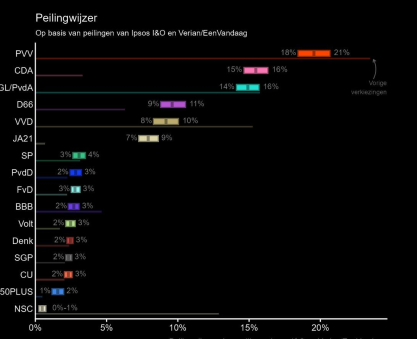

- If threshold is very low (Netherlands: 0.6%), the number of parties in parliament can get extremely high.

Duverger’s law: MAJ systems tend to have two-party systems.

- Modification: several regional two-party systems in the same country (Canada: Bloc Québécois, UK: SNP).

Two mechanisms behind this law

- Mechanical effect: below a certain threshold, parties win few or no seats.

- UK 2024: Reform: 14% of vote, 1% of seats; Greens: 7% of vote, 1% of seats.

- Psychological effect:

- Voters don’t want to waste their votes.

Dutch election next Wednesday

Here no majoritarian districts and no formal thresholds. Only an informal and low one, so everyone gets votes and there is no mechanical penalty (i.e. no Duverger’s law here).

Here no majoritarian districts and no formal thresholds. Only an informal and low one, so everyone gets votes and there is no mechanical penalty (i.e. no Duverger’s law here).

Party structure

- PR implies a list system. In order to be reelected, MPs need a good list position (less the case in open list systems).

- This gives party leadership an instrument for disciplining defecting MPs.

- In MAJ systems, MPs are less dependent on the party and can secure reelection on their own, party leadership lacks instrument for disciplining them.

- Extreme case: US, coherence of party groups in Senate and House of Representatives used to be low (not anymore).

- But: (governing) parties have other tools for enforcing party discipline (from allocating speaking slots to government positions).

Government structure

- MAJ normally leads to single-party governments: the party winning the election usually wins a majority of seats (UK, CAN).

- Thus, parties can in principle pursue their election program relatively unconstrained when in government → high accountability.

- That said, there may be other restrictions on governments, such as federalism and internal divisions (the party itself is a coalition of groups).

- PR normally leads to coalition governments of two or more parties.

- This means that no party can pursue their program in full.

- Sometimes divisions in parties can make things difficult even in majoritarianism→e.g. Brexit.

Government accountability

- Single-party governments in MAJ mean clear accountability: voters always know who is in charge and thus responsible.

- Principle of MAJ: The election as a referendum on the performance of the government: Throwing the rascals out.

- Power fully changes hand on a regular basis.

- Coalition government in PR systems means that it is much more difficult to attribute responsibility.

- Often, it is almost impossible to kick certain pivotal, centrist parties out of government (except by kicking them out of parliament)..

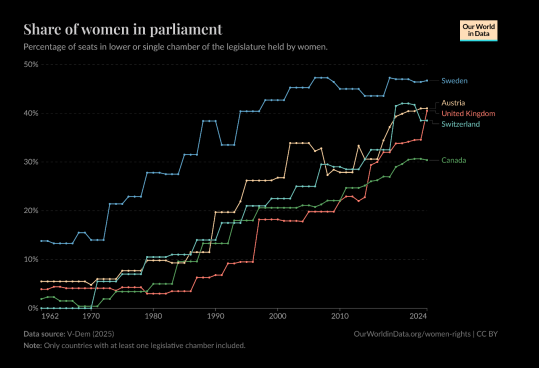

Descriptive representation

- Generally, the list dimension of PR allows parties to impose quotas on themselves in order to guarantee regional representation an/or to increase the share of female MPs, minority MPs, working class MPs etc.

- More difficult under majoritarianism, where candidate selection is often local (more on this in session 10 on parties).

- That said, MAJ systems do not necessarily perform worse with regard to the top jobs. Also, PR introduces its own biases (e.g. in favor of party insiders).

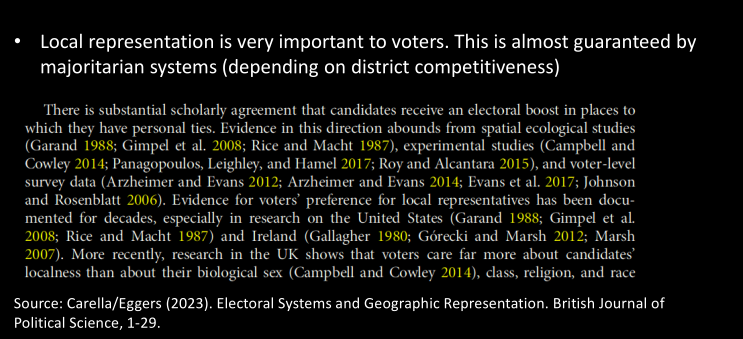

Exception: geographic representation

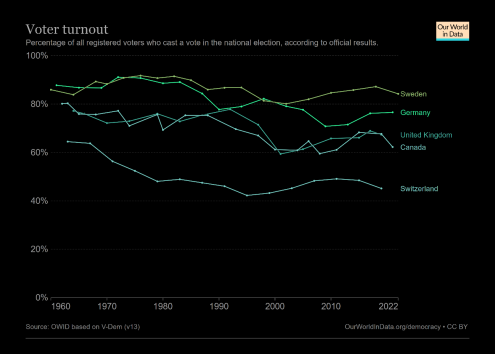

Political participation

- In MAJ, many districts are not competitive → they are always won by the same party with a large majority.

- Hence, little incentive to turn out (or to campaign) in these districts, political competition focuses on decisive Swing districts.

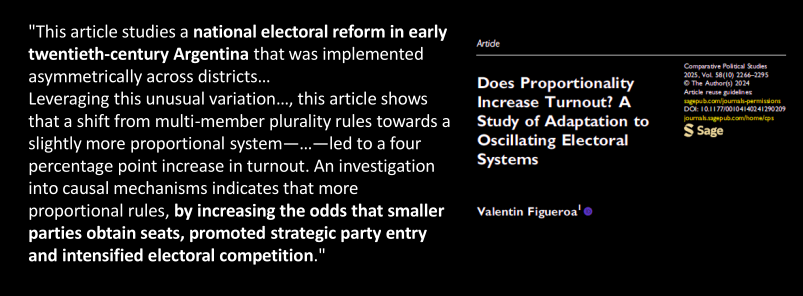

- In PR, every vote counts for the final result, local minorities have the same incentive to turn out as everybody else.

A recent study

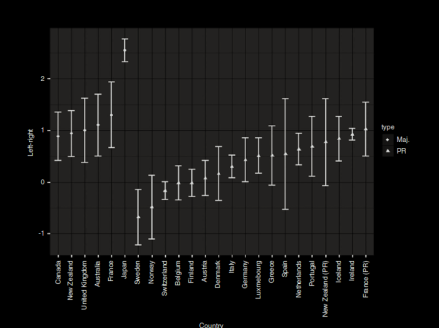

Government ideology (Döring/Manow)

- Döring and Manow argue that Majoritarianism tends to produce more right-wing governments, PR tends to produce more left-wing governments.

- Of course, if this is true, it will have effects on outcomes (economic policies, social policies, environmental policies…).

Potential explanations

- Strategic voting by middle class voters → how people vote.

- Anti-urban bias of majoritarian systems → how votes are translated into seats.

- Fragmentation of the right → how seats are translated into government positions.

Strategic voting by the middle class

- In PR, different social groups have their own parties.

- Interest aggregation occurs in coalition agreements after the election.

- Centrist parties are willing to enter center-left coalitions as veto players In MAJ, there are only two parties, no centrist parties.

- Interest aggregation occurs in parties before the election.

- Centrist voters fear that they cannot veto left purists in a left government.

- When they don’t have their own party they tend to vote for the right.

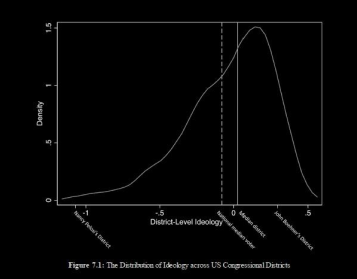

The anti-urban bias of majoritarian systems

- On average, left parties waste more votes when they win a district.

- This is because their voters cluster so heavily in big cities.

- Hence, with 50% of the vote, urban parties typically win less than 50% of seats.

- Also holds at presidential elections, see Bush v. Gore 2000, Trump v. Clinton 2016.

The distribution of district ideology in the US

Fragmentation of the right

- Historically main example: Scandinavian countries.

- In Protestant countries: strong, unified labor movement, divisions on the right over urban-rural or religious policies → more parties.

- Formal or informal rules often give right to form a government to biggest party.

- The more parties in a coalition, the more difficult it is to manage.

- This is a bit outdated, the left-wing is now fragmented as well.

Empirical analysis

- How do they measure a party’s left-right position?

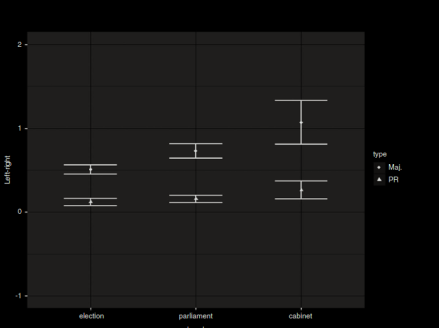

- How do they measure the voters’/parliaments’/cabinets’ left-right position?

- They use expert readings.

The right bias of MAJ

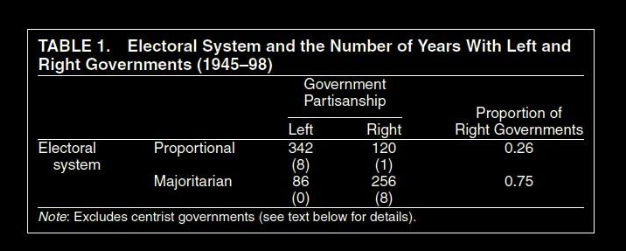

Other data confirms this

The bias on 3 levels of analysis

Summary

- H1: Voters in MAJ vote systematically to the right of voters in PR → supported.

- H2: For the same vote share, right parties get a higher (and left parties a lower) seat share under MAJ than under PR → supported.

- H3: Greater fragmentation on the right makes it more difficult to form right-coalitions under PR → only partly supported, fragmentation hurts both camps on both systems.

Endogeneity?

- What if left governments introduce PR and right governments keep majoritarianism?

- This analysis treats electoral systems as exogenous. However, it may be that countries with a stronger left were more likely to adopt PR.

- This is a problem of endogeneity.

Conclusion

- Electoral systems can contribute to explaining a huge number of differences between different countries.

- However, there will often be other, probably more important explanations.

- Even in the strongest case, party system structure, PR can explain that more than 2 parties emerge, but not, which parties will emerge.

- Still, institutionalist explanations are attractive, because institutions can be changed: countries can switch from MAJ to PR or vice versa –> raises the question why countries do this (or not).