Autocracy

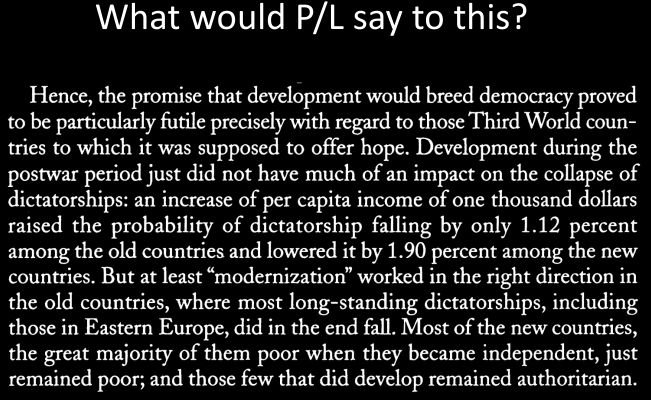

Applications of modernisation theory

- What does this tell us about contemporary cases of economic development in autocracies?

- China.

- Saudi-Arabia.

- What does this tell us about recent democratisations?

- The Arab spring.

- What does this tell us about contemporary cases of democratic reversal?

- Hungary.

- Turkey.

- India.

- USA.

China

Membership in the W.T.O., of course, will not create a free society in China overnight or guarantee that China will play by global rules. But over time, I believe it will move China faster and further in the right direction, and certainly will do that more than rejection would. By joining the W.T.O., China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products; it is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom. The more China liberalises its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people… And when individuals have the power, not just to dream but to realise their dreams, they will demand a greater say. The Chinese government no longer will be everyone’s employer, landlord, shopkeeper and nanny all rolled into one. It will have fewer instruments, therefore, with which to control people’s lives. And that may lead to very profound change.

- Bill Clinton, 2000.

For now, he has been wrong (25 years). And Limongi et al. would have helped predict this:

Saudi-Arabia and the Arab Spring

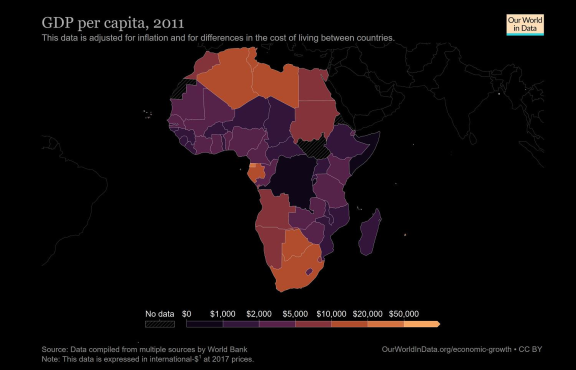

- GDP per capita probably not the ideal measure for capturing modernisation theory: Countries can be rich without developing a broad middle class.

- P/L, FN 10: The sample we describe here and use throughout does not include six countries that derive at least half of their income from oil revenues.

- If we stay only with the Arab Spring, what happened in Libya or Egypt could be justified using modernisation theory as they were more advanced economically.

Democratic backsliding

- Is democracy truly unassailable in rich countries?

- Has the way in which democracies collapse changed?

- More on this in sessions 4 and 5.

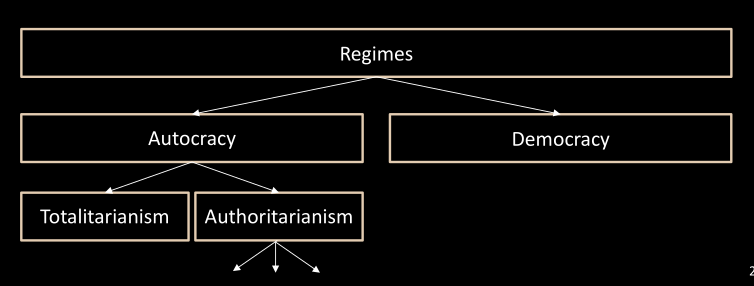

Defining autocracy

- In practice, autocracy and authoritarianism are often used interchangeably. In this lecture, we will try to stick to the following operationalisation:

So?

- Often defined negatively:

- Autocracy = absence of democracy

- Lindstaedt, p. 104: Authoritarian regimes are defined as regimes that have no turnover in power of the executive.(Remember Przeworski: Democracy is where parties lose elections).

- Gerschewski: It might be safe to say that the history of political ideas is by and large the history of democratic ideas. (Gerschewski, J. 2023. The Two Logics of Autocratic Rule. Cambridge, p.28).

- The variety of non-democratic regimes is much wider than the variety of democracies:

- Absence of competitive elections like in China.

- And/or: absence of civil rights like in Iran.

- And/or: elected leaders have no real power like it happens in Iran as well.

- All of these can be true, sometimes only a few…

The problem of succession

- A challenge for all political regimes: how to organise the turnover of power without endangering the regime.

- Except in personalist regimes, there has to be succession as it should be independent from its leader. It relies on replacement. This is guaranteed in democracy.

- Democracy can be seen as a solution to this problem: Because power is always temporary (until the next election), you can afford to hand it over to your opponent (and fight for winning it back).

- An aspect particularly emphasised by minimal definitions of democracy (Schumpeter/Przeworski).

- Democracy is when parties lose elections.

Succession in democracies

- In democracies, there are mechanisms for replacing party leaders that have become a burden on the party (Liz Truss had to resign as UK prime minister after 7 weeks).

- Presidential systems typically impose term limits.

- Even democracies run into the problem of how to get rid of leaders:

- Sometimes very strong incumbency advantages: in the US senate, the longest serving senator was elected in 1980, 6/100 senators are older than 80→gerontrification.

Succession in autocracies

- Particular challenge for autocracies: how to organise the turnover of power without competitive elections.

- Last week Przeworski/Limongi: a crucial moment which may lead to the advent of democracy.

- Autocracies dont have elections (main instrument).

- The incumbent powerholder may die/become old or ill/may become unpopular (with elites).

- And there is no organised opposition or way to force replacement inside the regime.

- This can threaten the stability of the regime.

- Autocracies seek organised certainty, they want to avoid ruled open-endedness (Gerschewski 2023, p. 4).

- Therefore, there is no regular turnover of power and no routine in dealing with uncertainty.

- Thus, the moment of uncertainty after a leader dies is particularly challenging.

- One solution is picking the oldest son, if he’s competent enough (recent innovation).

- This happens with any non-democratic organisation and isn’t limited to regimes.

The catch-22 of autocratic succession

The core problem of medieval succession politics finds echoes in the contemporary world. In today’s authoritarian regimes, the challenge is the same as in Europe’s past: to groom a successor who can placate the elites without risking that this successor will hasten the power transfer via a coup. Faced with this choice between a rock and a hard place, most contemporary authoritarian rulers choose not to groom a successor for fear of the Crown Prince Problem. One of the consequences is that many dictatorships do not outlive the death of their first leader.

Types of Non-democracies

- Totalitarianism

- Authoritarian Regimes

- Personalist dictatorships.

- Single-party regimes.

- Military regimes.

- Absolute monarchies.

- Competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky/Way).

Totalitarianism

- Distinguished from an ordinary tyranny.

- In these cases there is no ideological ambition, just to lead and represent the country while living a chill life. As long as the population doesn’t touch the regime they aren’t bothered (depolitisation of society). But this isn’t the case in totalitarianism, there’s great political mobilisation.

- A regime that seeks to fundamentally transform the structure of society, including by means of violence and terror to create a new human.

- Replacing religion and other collective organisations with their own (Hitlerian youth).

- E.g. 1920s.

- …a regime, a movement, a mentality, and an aspiration that goes beyond the limits of politics to encompass the whole of society, culture, and human life by negating the autonomy of domains such as science, religion, or art. (Hassner, S. 2011. “Totalitarianism”. In: Badie, B., Berg-Schlosser, D., & Morlino, L. (Eds.). International Encyclopedia of Political Science. SAGE.

- Everything becomes part of the regime’s totalitarian ambition to impose one worldview.

Examples

- Fascism (Germany 1933-1945, Italy 1922-1944).

- The Soviet Union under Stalin.

- North Korea today.

- Afghanistan under the Taliban.

- Totalitarianism is a heavily contested concept because people disagree whether it is legitimate to treat Nazism and Stalinism as instances of the same type (see our discussion of typologies last week).

- This happens a lot in social sciences, the terms carry a bagage from their origin story. This concept comes from the early Cold War, when USA switched from fighting fascism to communism.

- Stalinism didn’t engage in genocide in the same way the nazis did (technically it wasn’t as systemic). They still did reeducation camps and created a new human and society, etc.

- This happens a lot in social sciences, the terms carry a bagage from their origin story. This concept comes from the early Cold War, when USA switched from fighting fascism to communism.

Authoritarianism

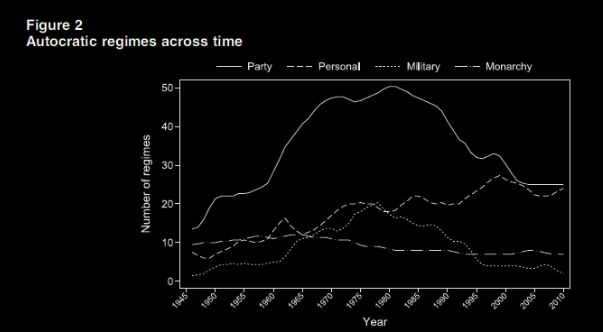

Across time

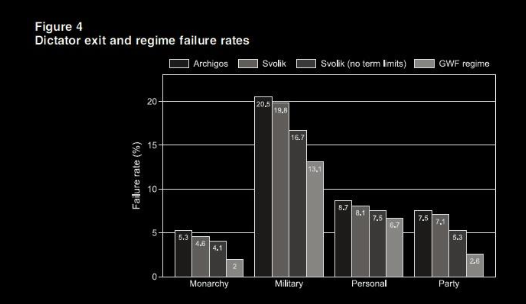

Personalist dictatorships

- We define personalist regimes as autocracies in which discretion over policy and personnel are concentrated in the hands of one man, military or civilian. (Geddes et al. 2014, p. 319).

- Not necessarily the leader of a dynasty.

- An individual leader is at the center of the regime.

- Other institutions (e.g. parliaments, the military) may exist, but are clearly subordinate to the leader.

- Often, the leader is an officer, but is unconstrained by other officers.

- Has become steadily more important since WWII.

- Vulnerable to the problem of succession (e.g. Venezuela).

- When Chavez died the opposition tried to overthrow the regime but Maduro succeeded him.

- Examples:

- Belarus.

- Azerbaïdjan.

- Russia.

- Iraq under Saddam Hussein, Libya under Qaddafi.

Single-party regimes

- A deeply institutionalised system.

- Relatively clear lines of accountability.

- Can have term limits (e.g. China pre-Xi).

- The most important position in these regimes is the leadership of the party, not the formal leadership of the country.

- E.g.: Khrushchev was General Secretary of the Communist Party but never Head of State of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev only became head of state in 1988.

- Relatively immune to the problem of succession, party can force unpopular leaders out (e.g. in Soviet Union).

Examples

- Communist regimes in Eastern Europe pre-1990.

- China post-Mao (and pre-Xi?).

- Vietnam.

Military regimes

- we distinguish ‘military rule,’ by which we mean rule by an officer constrained by other officers—sometimes labeled rule by ‘the military as an institution’—from rule by a military strongman, (Geddes et al. 2014, p. 319).

- Arises with a coup to displace civil regime.

- Has a group of leaders, not a single person.

- Common during the cold war, typically in Latin America (Juntas), often supported by the US or the Soviet Union.

- Usually relatively short-lived, transforms into a different form of authoritarianism or into democracy.

- Lowest ambition of transforming society, they just want stability and not politicising the military. Doesn’t mean they’d like to introduce democracy though, they are okay with finding a civilian leader and then retreat as a damocles sword.

- Hence, problem of succession less problematic.

- Examples:

- Greece 1967-1974.

- Many Latin American countries in the 1970s and 1980s.

- E.g. Argentina 1976-1983 (Przeworski/Limongi last week).

- South Vietnam during the Vietnam war.

- Myanmar.

- Many recent military coups in the Sahel.

Absolute monarchies

- A monarch from a ruling family rules the country, either directly or by selecting the cabinet and the prime minister.

- Not personalist, constraints on the leader.

- The other members of the family retain influence and constrain the monarch.

- Usually long-lived, the problem of succession is largely solved.

- Examples:

- Saudi-Arabia.

- Qatar.

- United Arab Emirates.

- Jordan.

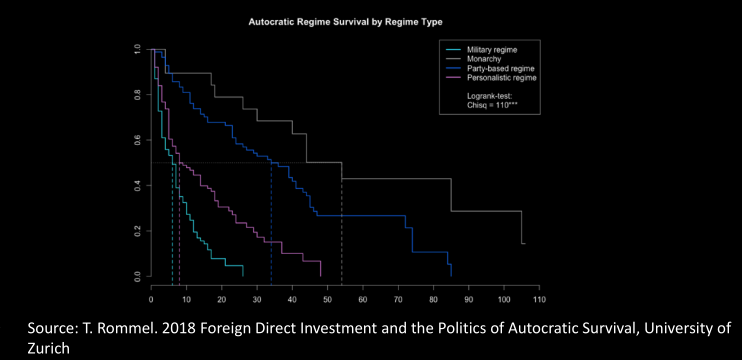

Autocratic survival

Some regimes just didn’t colapse because of intervention such as the URSS with some of its satellites. Most regimes eventually go trough changes such as monarchy→constitutional monarchy.

Some regimes just didn’t colapse because of intervention such as the URSS with some of its satellites. Most regimes eventually go trough changes such as monarchy→constitutional monarchy.

Do regimes fall after a leader exit?

Monarchies survive pretty easily if there’s a son f.ex.

Monarchies survive pretty easily if there’s a son f.ex.

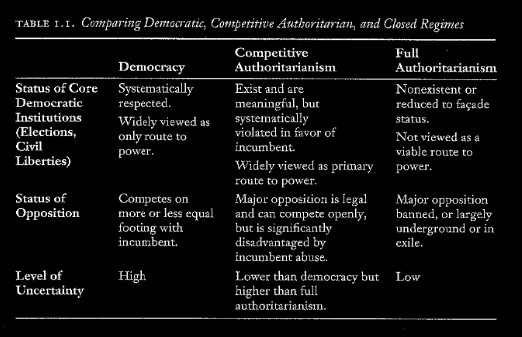

Competitive authoritarian regimes

Rather than ‘partial’; ‘incomplete’, or ‘unconsolidated’ democracies, these cases should be conceptualised for what they are: a distinct, nondemocratic regime type. People tend to say in-transition democracy or things like that by adding adjectives to the word democracy as these regimes aren’t classified. But this implies they will change, and this isn’t necessarily true in most cases. The lesson is that there is a new type, a new concept that should be used.

Definition

Competitive authoritarian regimes are civilian regimes in which formal democratic institutions exist and are widely viewed as the primary means of gaining power, but in which incumbents’ abuse of the state places them at a significant advantage vis-à-vis their opponents.

- civilian → Not military.

- Primary means of gaining power → not Monarchy.

- Relationship to personalist and single-party regimes more ambiguous.

- If there is no opposition party it can still be a civil rights activist f.ex. But in these types of regimes the main enemy is the opposition party leader. If there is no opposition it’s not a competitive authoritarian regime of course.

The importance of concept formation

- If authors introduce a new type, they have a heavy burden of proof that this is necessary.

- Why can this type not be subsumed by the existing types?

- Need to demonstrate:

- it is not full autocracy.

- and yet, it is not democracy either.

Incumbents are forced to sweat

- In full authoritarianism we would think of revolution as the way of taking power.

Not an autocracy

- A procedural minimum conception of democracy.

- the existence of a reasonably level playing field.

- The latter condition is violated in competitive authoritarianism.

- The other conditions are violated in pure authoritarianism (e.g., no elections, fraudulent elections, no civil liberties).

Not a democracy either

- Remember Przeworski: Democracy is a system in which parties lose elections.

- L/W argue that Losing elections is not a sufficient condition for identifying a democracy.

- Competitive authoritarian regimes violate minimal democratic norms (hence the importance of using a procedural minimum conception of democracy).

Uneven playing field

Even in democracies, incumbency comes with several advantages:

- Governments can allocate resources strategically, e.g. to pivotal districts.

- Governments can give jobs or contracts to their supporters (clientelism).

- It is very difficult to clearly separate government communication from party communication.

- Governments can use the international stage for domestic purposes.

- In some systems, governments can strategically time elections…

- This is much more severe in competitive authoritarianism due to:

- uneven access to resources.

- uneven access to the media.

- uneven access to the law (→ see session 8 on veto players).

- E.g. party registration laws like with the mayor of Istanbul in Turkey.

Why not just in between?

We can’t really give it a number scale all the 5/10s wouldn’t have the same story of inner working necessarily and that isn’t coherent or useful.

What do we gain?

- Competitiveness is a substantively important regime characteristic that affects the behavior and expectations of political actors. … governments and opposition parties in competitive authoritarian regimes face a set of opportunities and constraints that do not exist in either democracies or other forms of authoritarian rule.

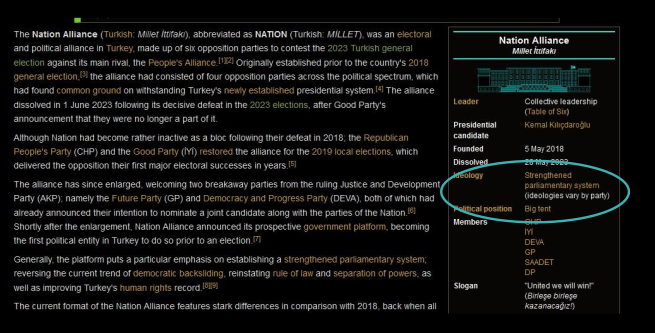

- Observe the behavior of Erdoğan and of the Turkish opposition before the 2023 election.

- It wouldn’t be easy to understand why they (opposition) believe in elections without the concept of competitive authoritarianism.