Democracy

Concept formation

- Comparative politics is to an important degree an endeavour in concept formation.

- We need to develop terms (concepts) that allow us to systematically describe and analyse the world.

- A lot of disagreement in comparative politics is about the proper definition and application of concepts.

- What do we mean by peace, democracy, the rule of law and so on?

- This also happens with party labels, could we define the republicans as the party of the right and the democrats as the party of the left according to European standards?

- These are essentially contested concepts: their proper use … inevitably involves endless disputes about their proper uses (Gallie, W.B. 1956. Essentially Contested Concepts, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56, pp. 167–198.).

- In other words, it’s part of their definition for people to argue about them. We agree that there’s not a correct answer.

The comparativists’ best friend: the typology

- There is often an immense variety of institutional formations: every electoral system/party system/legal system is different… When comparing a set of countries, it is imperative to classify them.

- We want to organise this variation…

- To handle it.

- To improve our understanding of internal logic of institutional setups.

- Therefore, we build typologies:

- All members of the same type are sufficiently similar on the dimension that we use to create the typology.

- Members of different types are clearly distinct on the dimension that we use to create the typology.

- There is some internal logic of the types that generates the stability of the typology.

- There has to be a logic to whether something is in a box or not. It has to be useful, not based on arbitrary criteria.

Some typologies

- Religions can be classified as monotheistic or polytheistic.

- Architectural styles can be classified as Romanesque, Gothic, Baroque and so on…

- Economic systems can be classified as capitalist or socialist.

Defining democracy

Government of the people, for the people, by the people. This quote is, according to Perez-Linan, (p. 87) an empty signifier.

We will now look at procedural definitions, since they only concern themselves about the institutions that distribute power. They do not look at what the power is being used for.

Minimalist definitions

- Joseph Schumpeter: that institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s vote. (Schumpeter, J. 1943. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy).

- It’s kinda like a market economy where products struggle to be bought (chosen) by people, but we are instead electing leaders.

- Adam Przeworski: Democracy is a system in which parties lose elections. (Przeworski, A. 1991. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America).

Expansive definitions

Here we look also towards the rules/preconditions of the competition. According to Levistky→modern democratic regimes all meet four minimum criteria:

- Executives and legislatures are chosen through elections that are open, free, and fair;

- Everyone has to be able to be a candidate. F.ex: in Iran elections are competitive but not everyone can participate as a candidate (religious committee decides).

- virtually all adults possess the right to vote;

- political rights and civil liberties, including freedom of the press, freedom of association, and freedom to criticise the government without reprisal, are broadly protected; and

- elected authorities possess real authority to govern, in that they are not subject to the tutelary control of military or clerical leaders.

- In Iran elected officials are subject to religious authorities.

Democracy as an empirical question

In comparative politics, we are not primarily interested in defining democracy theoretically, but in measuring and comparing it empirically. Comparativists ask questions such as:

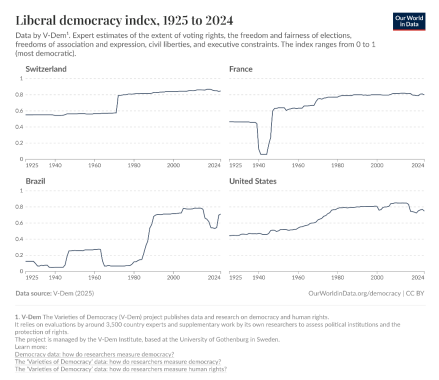

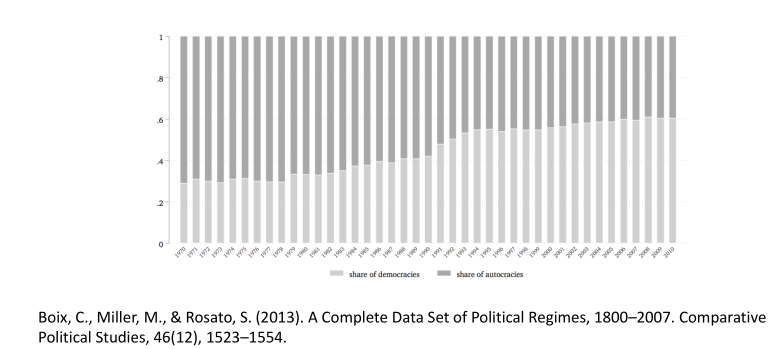

- Is democracy on the rise or in decline across the world?

- Does membership in international organisations affect how democratic a country is?

- What is the relationship between economic prosperity and democracy?

- Do democracies provide public goods better than non-democracies?

To answer these questions, we need to measure democracy!

Continuous or dichotomous

Can a country be more or less democratic? Or is it simply democratic or non-democratic?

- Continuous: define an ideal type which countries reach to a different degree.

- Better, we set an ideal and see how countries compare to it. Less black and white, more gray.

- Dichotomous: define a list of criteria (can be one criterion), all criteria have to be fulfilled, otherwise it is not a democracy.

- This would mean that the HC in the 1960s would be in the same box as Italy in the late 1930s if we use an expansive definition of democracy.

Example: continuous

Example: dichotomous

The problem of measurement

No matter what definition, it is necessary to obtain information about the respective countries. To measure the degree of democracy, there are mainly two approaches:

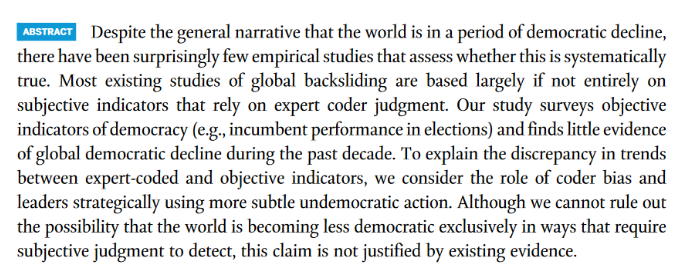

- Expert codings.

- Survey political science professors and/or experts, they will judge their country (ex.: V-Dem).

- The obvious critique here is that they are not neutral observers, but extremely implicated individuals. After all, it is their own country. They’d need to have more distance to eliminate the distortion bias in their perception.

- Objective measures.

- The issue is that changes outside of rules, such as the way laws are used, are not detected. Less reactive and immediate than expert codings.

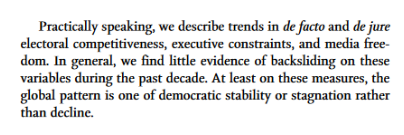

Objective measures

Mesures used by Little/Meng

- Electoral turnover: do incumbents lose elections?

- Executive constraints: are there term limits or other rules for executive succession?

- Media freedom: number of journalists who have been jailed and killed

Problem: can hardly be used to measure change within single countries (except for 3→media freedom). Backsliding does not immediately start with rules changing in many countries.

The in-between cases

It is easy to classify Norway or Belarus. The reading for next week aims to deal with the less clear-cut cases. How should we think about Hungary, India, or the current status of the United States? ⇒ These questions of measurement and operationalisation are also subject of Tutorial I-Democratic Backsliding, Institutional Change….

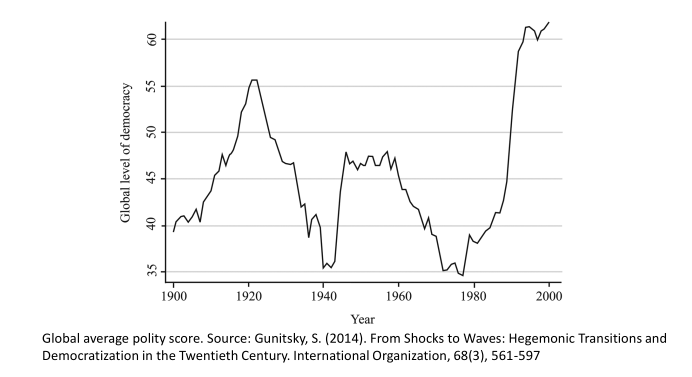

Waves of democratisation

How has democracy developed across the world?

Three waves

- First Wave, 1828-1926: North America, Western Europe.

- Reversal: 1922-42.

- Second Wave, 1943-62: Europe, Japan, Latin America, Africa.

- Reversal : 1958-75.

- Third Wave, 1974- : Southern Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe.

- Reversal: ?

Why waves?

How can we explain common developments across countries?

- A common shock to the international system (end of World Wars, collapse of Soviet Union, Oil crisis…).

- Contagion: neighbouring countries affect each other (snowball effect, domino theory).

- That’s how the USA thought communism spread between nations during the Cold War.

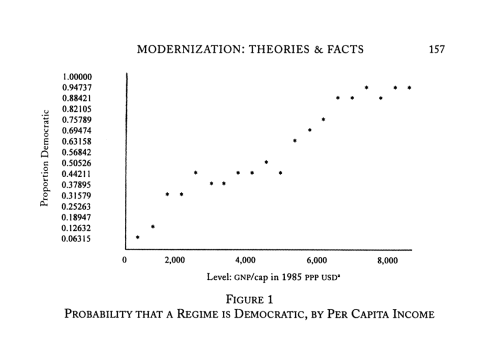

Very strong correlation between GDP and democracy

- Do rich countries become democracies?

- Do democracies only survive in rich countries?

- Or do democracies become rich?

The last mechanism creates a problem of endogeneity. X may cause Y, but Y may also cause X.

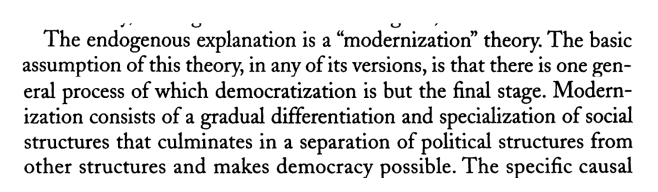

Modernisation theory

- S.M. Lipset (1957, 1959): The more well-to-do a nation, the greater the chances that it will sustain democracy.

- Mechanisms: A growing middle-class as important pro-democratic social group.

- Economic mechanism: growing material interest in self-governance and control of government. Wanting to protect gains.

- Cultural mechanism: growing importance of pro-democratic values, demand for participation in governance. Education and connection with democratic values.

What type of theory is this

The mechanism

Modernisation theory as structuralist theory

- Barrington Moore, 1966: No bourgeois, no democracy.

- Economic development goes along with structural changes in the economy and society:

- Declining importance of agriculture, growing importance of industry and/or services.

- Expanded division of labor, increased need for cooperation.

- Expansion of education facilitates communication, exchange, organization.

- Urbanization facilitates communication, exchange, organization.

- As a consequence, a growing number of people has a material interest in self-governance and a capacity to organise.

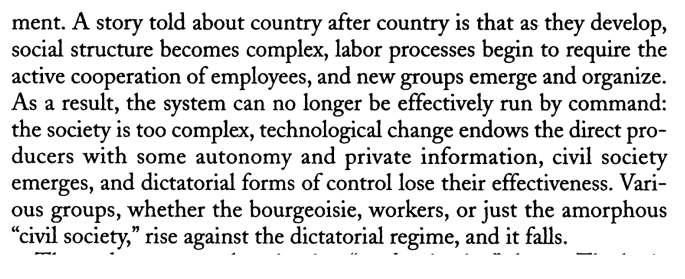

As a culturalist theory

- Economic development goes along with value change in the population:

- Self-expression values become more important.

- This concerns individual lifestyles but also participation in public governance.

- Economic modernisation goes along with ideological moderation.

- As a consequence, a growing number of people demands to be included in political decision making and is willing to accept political compromise.

Main findings: becoming a democracy?

Main findings: sustaining democracy

Basically the same arguments for the endogenous theory but kind of in a reversed mechanic. Plus, wealthy democracies can absorb shock and provide public goods which reduces loss of faith in the current system. This allows a solidification of the norms and rules in place as time goes by which makes backsliding (authoritarianism in the case of this paper), unlikelier.

Basically the same arguments for the endogenous theory but kind of in a reversed mechanic. Plus, wealthy democracies can absorb shock and provide public goods which reduces loss of faith in the current system. This allows a solidification of the norms and rules in place as time goes by which makes backsliding (authoritarianism in the case of this paper), unlikelier.