Theories of Negotiations

Typology of Negotiations

Two key types:

- Bilateral vs Multilateral negotiations.

- Distributive vs Integrative negotiations.

Bilateral negotiation

- Involve two actors seeking a mutually acceptable outcome.

- Characterised by interdependence despite unequal resources.

- Defined by formal equality.

- That’s the point of the system: sovereignty, UN charter→ basically respecting each country.

- Ex: Armenia-Azerbaïdjan.

- There is an international system composed of states. As an actor, it is possible to talk to others. When you have a lot of actors, it is not possible to do bilateral negotiations constantly. Some problems are global.

- Armenia wanted to bring in allies (e.g: France), the powerful one being Azerbaïdjan which didn’t want to.

- Multilateralising a conflict by bringing in the UN among others can also help draw a resolution or enforce peace.

Multilateral negotiations

- Multiple actors, multi-issue agenda, cultural diversity.

- Strategies include sequencing, persuasion, coercion, alliance-building.

- Weaker states often prefer multilateralism.

- Often take place in international organisations.

- Foster diffuse reciprocity through repeated interaction.

- See each other more→ understand each other (liberalism)→ more liberal approaches emerge between countries.

- Ex: Paris Agreement (2015).

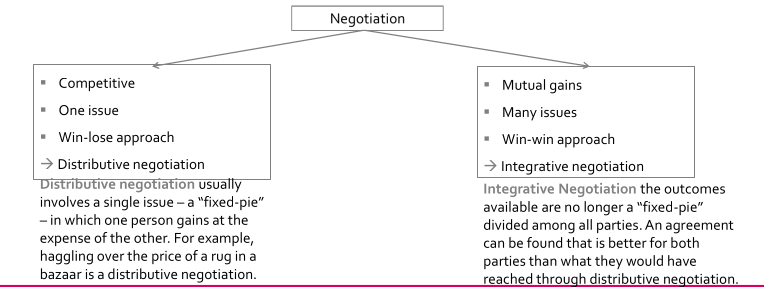

Distributive vs. integrative negotiation

- Distributive = Fixed pie, win-lose, coercion, salami tactics.

- Integrative = Expand the pie, win-win, creative problem-solving.

Distributive negotiation

- Win-lose, zero-sum outcomes.

- Parties act as adversaries.

- Information is withheld to maximise gains.

- Examples:

- Marketplace haggling.

- Territorial disputes (e.g., India–China border conflict).

- Trade tariff negotiations (e.g., US–China trade war).

Integrative negotiation

- Win-win, positive-sum outcomes.

- Parties collaborate as partners.

- Emphasis on information sharing and creative solutions.

- Examples: (Multilateral negotiations).

- Peace agreements (e.g., Camp David Accords).

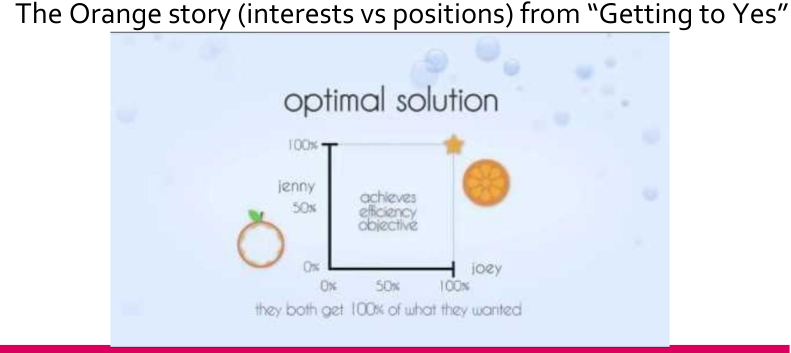

- Each wanted something different, both got what they wanted as it wasn’t incompatible. There were two pies, in a way.

- Climate negotiations (e.g., Paris Agreement).

- Peace agreements (e.g., Camp David Accords).

The Orange story

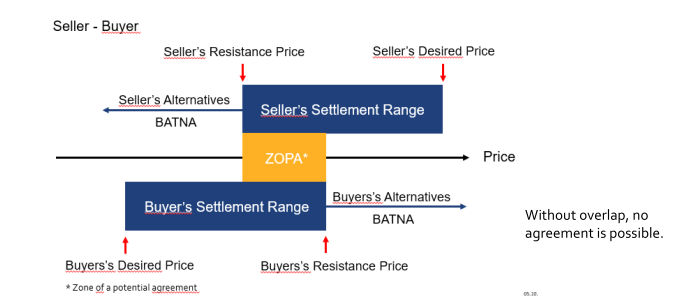

Key negotiation concepts

- The world of Negotiation theory is filled with popular concepts: Starting Point, Reservation Point (bottom line), Target point , Formula-detail, Institutional Context, Failed/Just Outcomes ….

- Amongst the most popular concepts, are:

- Zone of potential agreement (ZOPA) is the bargaining range where two or more negotiating parties might find common ground. The parties must have a common image of the outcome they want to achieve and the ZOPA typically includes at least some of the ideas and interests of each party to get there.

- Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) is the best and most advantageous alternative course of action for a negotiating party if negotiations fail and an agreement is not reached.

Theoretical Approaches to Negotiation

All these concepts derive from theories/approaches! Such as:

- Principled approach (interests VS positions)

- Structural approaches (power asymmetries, hard power).

- Strategic approaches (game theory, bargaining).

- Sequential/process-based analyses (phases of negotiation).

- Constructivist approaches (norms, values, culture).

- Behavioural & psycho-cognitive approaches.

- Historical sociology approaches.

Be careful:

- Dont get overwhelmed.

- Dive in→you can get lost.

- Each theory is just a different pair of glasses, depending on your needs as negotiators or students trying to make sense of negotiation.

- E.g: Cold War from realism (assured mutual destruction) or liberalism (interdependence economically and mutual profit from cooperation) to explain lack of war in Europe.

- The meaning of things such as power changes greatly and so does the conception of our world.

Principled approach: Getting to Yes

The Harvard Method

Developed by Fisher and Ury (1981). Four key principles:

- Separate people from the problem.

- Focus on interests, not positions.

- Position: manifestation of an interest in a concrete manner.

- Interest: underlying motivation, concern, and importance.

- Generate options for mutual gain.

- Base outcomes on objective criteria/standard.

Principled negotiation in practice

- BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement).

- Managing relationships and emotions.

- Use of perception, empathy, active listening.

- Ensures fair, sustainable agreements.

- Ex: Camp David Accords (shared interest: regional stability. But interest as security + recognition (ISR) VS reagining Sinai Peninsula territory (EGY)).

Limits of principled negotiation

- Describes the world as it should be, and not as it is.

- Oversimplification: does not take into consideration complexity of parties (States are not unitary actors).

- Interests can then change, unless you assume that cultural norms exclusively shape them (they also change either way).

- Relies on anecdotal evidence. Not much science behind it.

Structural approaches

- Negotiation reflects underlying power relations. Emphasises the role of economic, military, and political resources in shaping outcomes.

- Realist/neo-realist parallels.

- Key Authors: Hans Morgenthau, Henry Kissinger.

- Example: U.S.–China trade negotiations where economic and military power shaped outcomes.

Strategic approaches

- Focus on rational decision-making, game theory, and bargaining models. Strategic approaches use mathematical models to predict negotiation outcomes.

- Trying to predict whether the Soviet Union would or wouldn’t make more missiles if the USA did as well, e.g.

- Use of game theory models.

- Highlights rational choice.

- Key Authors: John von Neumann, John Nash, Thomas Schelling-

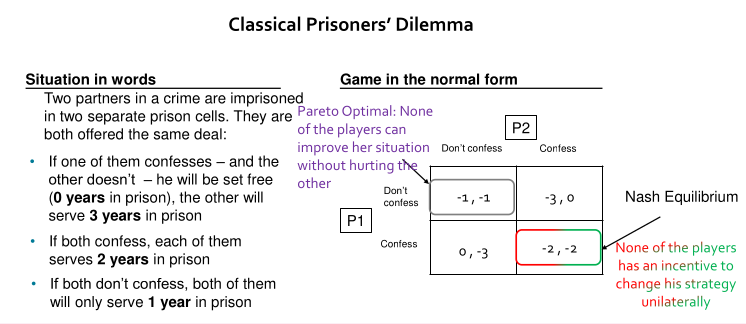

- Example: Cold War arms race and negotiations modelled as a Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Game theory in negotiation

- Developed by John von Neumann (1920’).

- The Prisoner’s Dilemma illustrates cooperation vs defection.

- Analysis of strategic decision-making and conflict of interests among the players.

- Result of the decision-making depends on the other players’ decisions.

- Strictly formalised by means of mathematical models.

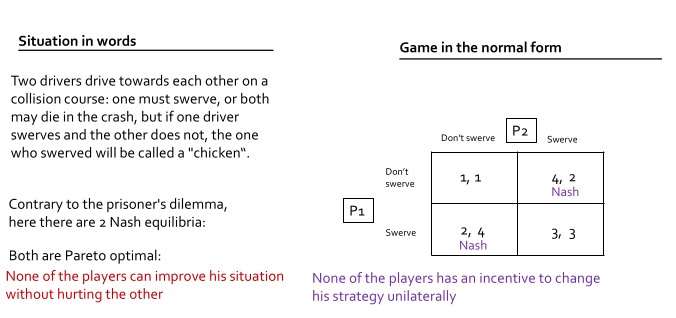

- There are other games such as the chicken game:

Limits of game theory

- Assumes rationality, overlooks trust and emotions.

- Explains outcomes but not values or norms.

- Everyone doesn’t think following the same system basically.

- Highly systematic but free of any consideration of process as practised in negotiation.

- E.g.: deciding to wait for new elections in a state before negotiating with it.

- Negotiation also requires concessions, trust, and face-saving.

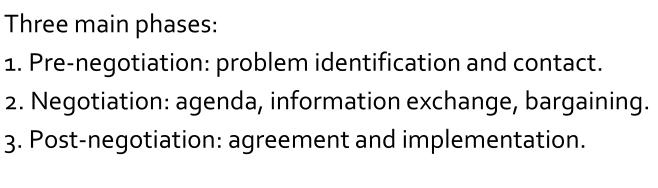

Sequential/Procedural approaches

- Analyses negotiation as a process with distinct phases: preparation, bargaining, and implementation.

- Negotiation as a sequence of concessions.

- Breaks negotiation into stages, allowing for targeted strategies at each phase (Ripeness theory, mutually hurting stalemate (MHS)).

- Each concession signals intent and encourages reciprocity.

- Key Authors: I. William Zartman.

- Example: Colombian peace talks.

- Reduce arms violence, many actors→big implementation phase.

- Reduce arms violence, many actors→big implementation phase.

Limitations

- Reality often more non-linear with overlaps and deadlocks.

- Risk: purely regressive bargaining vs creative solutions.

Constructivist approaches

- Normative, legitimising, and socialising aspects.

- Highlights the role of norms, values, identity, and social context.

- Negotiation is seen as a process of social construction.

- Constructivist approaches argue that negotiation outcomes are shaped by social context and collective identities.

- Negotiation builds its own culture of norms, ideas or gender.

- Interests are socially constructed, not fixed.

- Power is not just a mechanical transformation of ressource.

- Example: Lybia Intervention (2011). Adler Niessen & Pouliot , Negotiation as practice/Ars vivendi.